Regardless of how today's lunar landing attempt goes, India's lunar legacy is assured.

The nation's Chandrayaan-2 mission is scheduled to touch down near the moon's south pole between 4 p.m. and 5 p.m. EDT (2000 to 2100 GMT) today (Sept. 6), dropping a lander-rover duo onto the gray lunar dirt.

If the maneuver works, India will join a very select club. To date, only the United States, the Soviet Union/Russia and China have pulled off a soft landing on the moon. (The Israeli nonprofit SpaceIL and its partner, Israel Aerospace Industries, nearly joined this group in April, but their Beresheet lander crashed during its touchdown try.)

Related: Here's Where India Will Land on the Moon (and Why)

In Photos: India's Chandrayaan-2 Mission to the Moon

But India is no lunar novice. Chandrayaan-2's predecessor, Chandrayaan-1, helped reshape scientists' understanding of the moon, showing that a key exploration-aiding resource is widespread on Earth's nearest neighbor.

Chandrayaan-1, India's first deep-space mission, launched on Oct. 22, 2008, and arrived in lunar orbit a little more than two weeks later. Shortly thereafter, the orbiting mothership released the 64-lb. (29 kilograms) Moon Impact Probe (MIP), which slammed into the dirt near the lunar south pole.

The Chandrayaan-1 orbiter, meanwhile, continued studying the moon from above for the next 10 months using a variety of instruments. One of them was the Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3), an imaging spectrometer contributed by NASA.

In September 2009, the Chandrayaan-1 and NASA teams announced some exciting results: M3 had spotted the spectral signature of water across much of the lunar surface, with the abundance of the stuff increasing toward the poles (though it never gets too abundant, topping out at around 0.07%). And we soon learned that the MIP had detected H20 during the craft's descent as well — including some water vapor, the first time the gas had been found in the moon's wispy "exosphere" since the Apollo days.

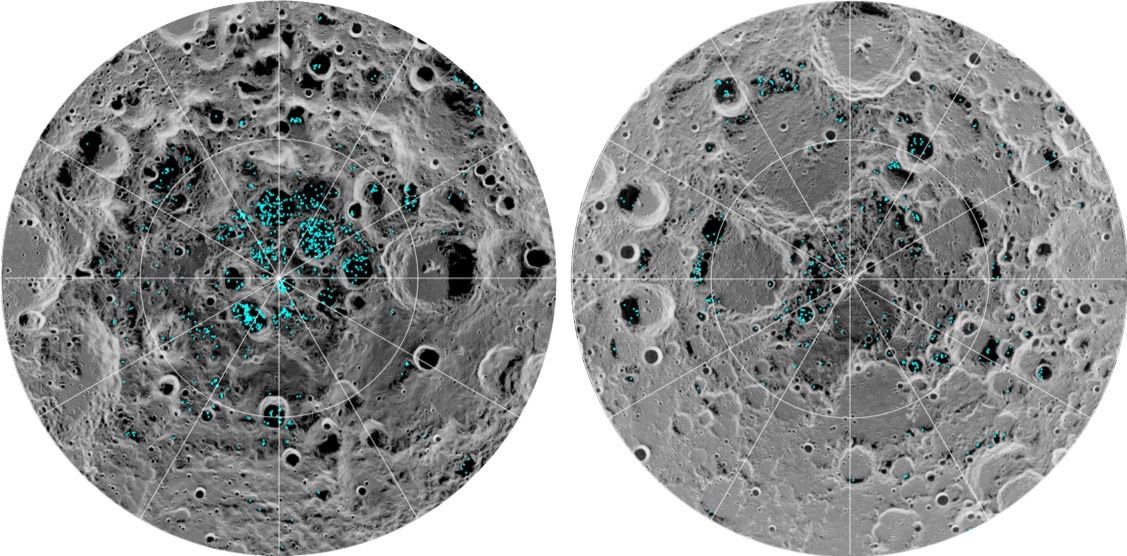

The raw M3 readings didn't indicate what form that lunar water takes — whether it's locked into minerals, for example, or exists as slabs of pure ice. But in 2018, researchers reanalyzed the M3 data and concluded that much of what the instrument spotted near the poles was water ice on the floors of shaded craters.

The rethink kicked off by Chandrayaan-1 and M3 has picked up considerable steam since the mission came to a premature end in August 2009. (The orbiter was supposed to operate for two Earth years but apparently succumbed to overheating.)

Related: The Search for Water on the Moon in Pictures

In November 2009, for example, scientists announced that NASA's Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) mission had detected significant amounts of water in a lunar plume. That plume came from an impact in the permanently shadowed floor of Cabeus Crater, near the moon's south pole. (The impactor was the spent Centaur upper stage of the United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket that sent LCROSS on its way.)

A year later, the LCROSS team determined that water ice made up a considerable portion of the regolith at the impact site: 5.6% by mass, plus or minus 2.9%.

The emerging picture suggests that water ice may be plentiful and accessible enough on the floors of permanently shadowed polar craters to significantly aid human exploration. Moon water can not only provide life support for pioneering astronauts, after all, but also, once split into hydrogen and oxygen, help refuel rockets and spacecraft.

Indeed, exploiting polar water ice is a key part of NASA's lunar exploration plans, which the agency is pursuing via a program called Artemis. NASA intends to land two astronauts near the south pole by 2024 and set up a long-term, sustainable human presence on and around the moon by 2028. But before any of that happens, the space agency will launch water-prospecting instruments aboard commercial lunar landers.

Chandrayaan-2 will provide useful information in this regard as well, if all goes according to plan.

The mission launched on July 22 and arrived in lunar orbit a month later. The Chandrayaan-2 orbiter has been studying the moon ever since, using a variety of instruments, including water-detecting gear.

Then, there's the surface element of Chandrayaan-2. The mission's targeted landing site is at 70.9 degrees south latitude, just 375 miles (600 kilometers) from the lunar south pole. No other mission has ever soft-landed so close to that spot. (Cabeus Crater sits at about 82 degrees south, but the LCROSS impactor's landing was decidedly not soft.)

Chandrayaan-2's lander, called Vikram, and rover, named Pragyan, will touch down just after dawn at their landing site. The robots will operate for about 14 Earth days, until the freezing temperatures of the lunar night do them in, as is expected to happen. (The moon completes one rotation every 28 Earth days, so its "day" lasts nearly a month.)

The orbiter's prime mission is scheduled to last two years.

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

https://www.space.com/india-moon-legacy-water-chandrayaan-1.html

2019-09-06 11:01:00Z

52780373331667

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar